Shared public value: a digital city differentiator

Over the past 20 years, cities have tended to look first to innovative uses of technology as a way to respond to urbanization challenges. Technology has been considered as a crucial weapon to fight against urban problems, such as the need for clean energy, waste treatment and urban mobility, as well as an instrument to deliver new and better services, to inform and communicate with citizens, and to create social and economic opportunities.

However, we are now recognizing that digital applications and platforms alone are not sufficient. Rather than identifying technology as the solution to urban issues, it should instead be seen more as a tool needed to deliver these solutions to the people who live in the city. In its place, the aim should be for a strategic, digital ecosystem that connects stakeholders, offers new perspectives, and supports a holistic approach to innovation and the development of digital city solutions.

Central to this new way of thinking is the concept of shared public value and how it is incorporated into strategic city planning. We believe that one of the most crucial challenges for the digital city planners of the future will be to address their policies towards the creation of a shared public value that in turn will lead to positive outcomes for all city stakeholders.

What is shared public value?

Shared value is the concept of linking business strategies and corporate social responsibility with private companies concurrently pursuing their own profit alongside the creation of well-being for people.

Public value is the value that an organization creates for people and the community.10 The idea of public value is to drive public policies towards the real needs of the communities, in both the short and the long term.

Shared public value is at the crossroads of these two fundamental concepts. It puts together the effective management of public organizations with the private management principles based on value creation, successful strategies and sustainable business models. A public organization can implement urban policies by adopting the innovative and inclusive business models of the shared value theory and the good management practices of the public value theory.

How to create a shared public value model

1. Strategic stakeholder collaboration

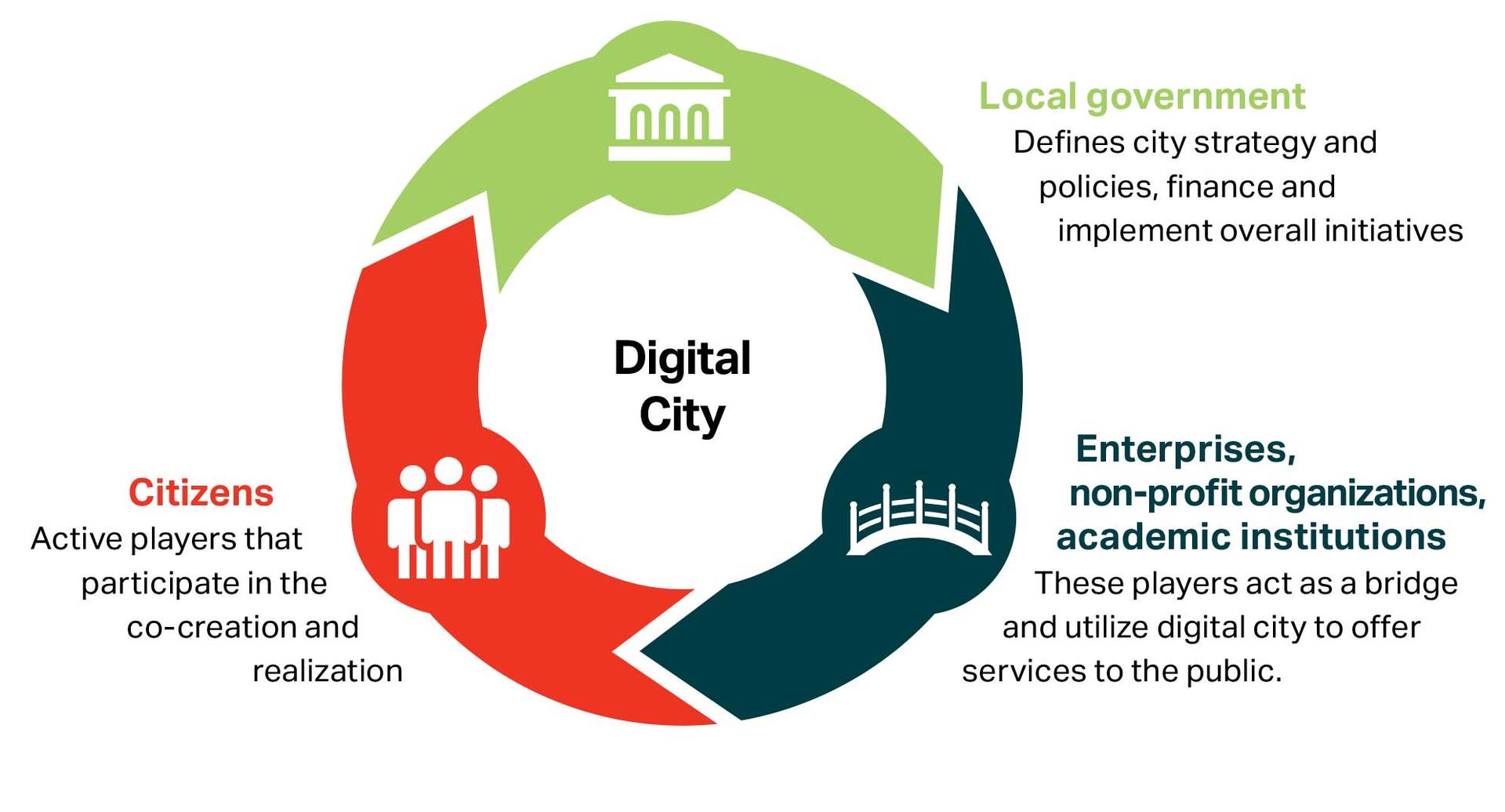

At the heart of shared public value is the need to overcome the traditional divide between the role of citizens, government and other public actors, private companies and non-profit organizations, and to develop interconnection and collaboration between all stakeholders. Figure 4 below describes how all the players are involved in the digital city implementation.

Shared public value is not created by a sole component of the digital city, but by the interaction of them all. Without effective digital city governance, initiatives and projects may not be driven towards well-defined and comprehensive goals. Without aware and involved citizens, the digital city applications and services could remain unused, not understood or neglected, producing little value.

A good example of strategic stakeholder collaboration in action can be seen in the Italian city of Genoa, which formed the Genova Smart City Association, a non-profit organization chaired by the mayor and includes elected representatives from all stakeholders. The association has the power to prioritize projects and to finance initiatives. It uses roundtables and living labs to consider the most important needs of citizens.

The idea to create an association was born from the necessity for a collective effort to launch the smart city initiative which at that time was still considered a novelty. However, the association encountered many problems in its functioning, owing to an inadequate governance framework. After years of ineffectiveness, the association rewrote its statute, better designing the powers and roles of different members of the association. The most important change was that the president of the association would no longer be the mayor, but a representative of the private members of the association, elected by all the members. This transformation allowed the association to pursue its objectives involving all the city stakeholders.

Similarly, Smart Belfast is a foundation in the U.K. joining all the players working for the smart city program, with the main aim to define common methods and resources for identifying, understanding and designing solutions for urban challenges. Belfast is a city that suffers from common problems of urbanism, but it also struggles with the fallout of its violent history. The Smart Belfast program is seen as a strategy aimed at reconciling all the citizens with themselves and with the city. Using living labs, the Smart Belfast initiative involves citizens and SMEs to experiment with smart solutions in a real setting. It is also a way to face the city’s historical problems and to suggest transformative solutions for the most marginalized neighborhoods and citizens. Technology and social debates cooperate to deliver shared public value to all.

2. Benchmarking against international frameworks

Even if each city can define its own priorities, it is useful to benchmark digital city policies with international frameworks. There are numerous digital city frameworks available both in scientific literature and those issued by consulting firms. However, one of the most authoritative models is the OECD Principles of Urban Policy.

This model aims to define a set of general principles driving local governments to implement good policies in public interest. It is a methodological tool that can be applied to different types of urban policies, and is based on three pillars: strategy, stakeholders and scale (see Figure 5).

The OECD Principles on Urban Policy are already impacting a number of countries. For example, the Czech Republic has adopted the principles to drive its cities to implement sustainability through the Smart Czechia Concept. It is interesting to note that the central government – the Ministry of Regional Development – drives the smart city strategy at the national level. The aim of this initiative is to overcome the underdevelopment of smaller cities, and to create a shared vision supporting the sharing of resources and best practice. The Czech cities are not able to implement a robust and effective smart policy by themselves, so the question is to understand how the national structures can support the local capacity to pursue more just, green and productive cities. To reach its objective, the Ministry is planning a pathway involving the members of the European Urban Knowledge Network, a strategic knowledge network uniting European national governments to promote sustainable urban development.

3. Identifying and addressing key challenges

Before realizing single projects, local governments looking to implement a successful digital city should first design a strategic plan focused on the community’s priorities. However, in order to reach the desired outcomes in implementing their digital city strategies, local governments should first identify and address a number of critical challenges.

- Funding and financing: Realizing a comprehensive digital city requires significant investment, and as such local governments need to define a specific strategy to collect the financial resources needed to allow full implementation. Through an effective business plan, the digital city can achieve financial self-sufficiency, reducing its dependence on external financial resources.

- Orchestration, integration and trust: As the digital city is a complex ecosystem, it requires robust governance architectures and mechanisms to drive the city towards the highest shared value creation. This requires strong communication in order to achieve an open and trusting dialogue with all citizens. Local governments need to orchestrate this communication on four levels: political, legal, operational and social.

- Cultural change management: Implementing a smart or digital city program is a political action requiring the citizens’ awareness and involvement, not only in prioritizing and planning the projects, but also in behaving appropriately. Two main aspects can be considered: improving citizens’ awareness and use of digital technology, and increasing their active contribution to reducing the city’s environmental footprint.

- Digital divide: Differences in the levels of digital literacy for citizens create a digital divide in respect to using digital city services, which in turn increases rather than reduces inequalities. Specific educational programs should be addressed to vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, those with limited education and citizens living in more disconnected areas.

- Privacy and security: It is important that data collection and retention is open and transparent, backed by appropriate privacy regulation. Digital cities across the world are committed to opening their data and putting it at the disposal of citizens, which in turn leads to better oversight of public administration works.

Conclusion

The implementation of a digital city plan is a crucial challenge for cities all over the world. It rests on the creation of a shared digital infrastructure to deliver useful and tailored digital services that will help alleviate some of the most important urban problems impacting the quality of daily life for citizens. That said, a successful digital city based on the concept of shared public value needs to take into account a number of key factors.

- Focus on people-driven outcomes, not on technology. Often, it seems that the aim of a digital city is to be digital – that is, to implement digital infrastructures and applications. However, these should be seen only as the tools necessary to deliver value to the citizens of the city.

- Adopt appropriate indicators. For instance, instead of using only digital infrastructure indicators to measure the digital city, cities should focus on measuring the benefits by adopting indicators such as access to digital services, employment rates, public engagement, and levels of public satisfaction.

- Think about extension, scalability, replicability. A winning digital city strategy needs to extend digitalization and its benefits to all citizens, designing digital projects with scalability and replicability built in.

- Ensure inclusion as a keyword. Digital services should be for all, not for a minority. They should impact the highest number of citizens, creating the highest public value (Wiig, 2016).

- Consider local needs. Even if digital and smart cities are a global phenomenon, it is necessary to tailor the digital city strategy to the specific needs and profile of each city. Urban problems seem similar but assume different features in different cities.

- Emphasize data-informed decision making. This can increase transparency and in return improve trust. Communication is key in the construction of a city image that is simultaneously innovative, competitive, effective, as well as safe, livable, equitable and sustainable.

- Stress the importance of outcome. When planning a digital city initiative, local governments should define the goals they want to reach from the beginning, and concurrently design a set of indicators able to measure if and how these goals have been reached. The evaluation of outcomes should be an integral part of the digital city.