Designing public spaces through people and data

One of the key debates to emerge from the coronavirus pandemic is how it has changed our perspective about the role of cities and their open spaces. As cities return to normality, and as urban centers continue to dominate and adapt, we need to ensure that public spaces are effective, accessible and inclusive — maximizing their value for all citizens. To achieve this, we need to look at the next generation of public spaces that are people-centric, adaptive, and explore ways to integrate data and technologies into our physical realm.

The fight for public space — doing more with less

Urban population growth is happening at an epic rate. As more people are set to inhabit urban centers (existing and upcoming), they will also face the intrinsic challenges of city life. This can for many people be a mixture of alienation, isolation, fear, congestion and pollution; instead of community, participation and pleasure.

One cause of these challenges in highly dense cities is the scarcity of space, coupled with development pressure. A negative consequence of this situation, revealed by a recent survey, is that in less than one generation, physical activity has dropped by 45 percent in Mainland China,8 while in the U.K. and in the U.S. there has been a drop of 20 percent and 32 percent, respectively in two generations.9

According to a 2017 Civic Exchange Study, Hong Kong has only 2.7 m2 of public space per capita, a figure lower than other major Asian cities such as Tokyo (5.8 m2), Seoul (6.1 m2), Shanghai (7.6 m2) and Singapore (7.4 m2). New York, also known for its high land price, has over 10 m2 (107.6 ft2) of public space per capita.

In this current and even more alarming future scenario, public spaces are a critical asset for our cities more than ever before and a key factor for the citizens’ physical, mental and emotional well-being. The objective to do more with less will be a key challenge to urban designers in the push for next generation public spaces.

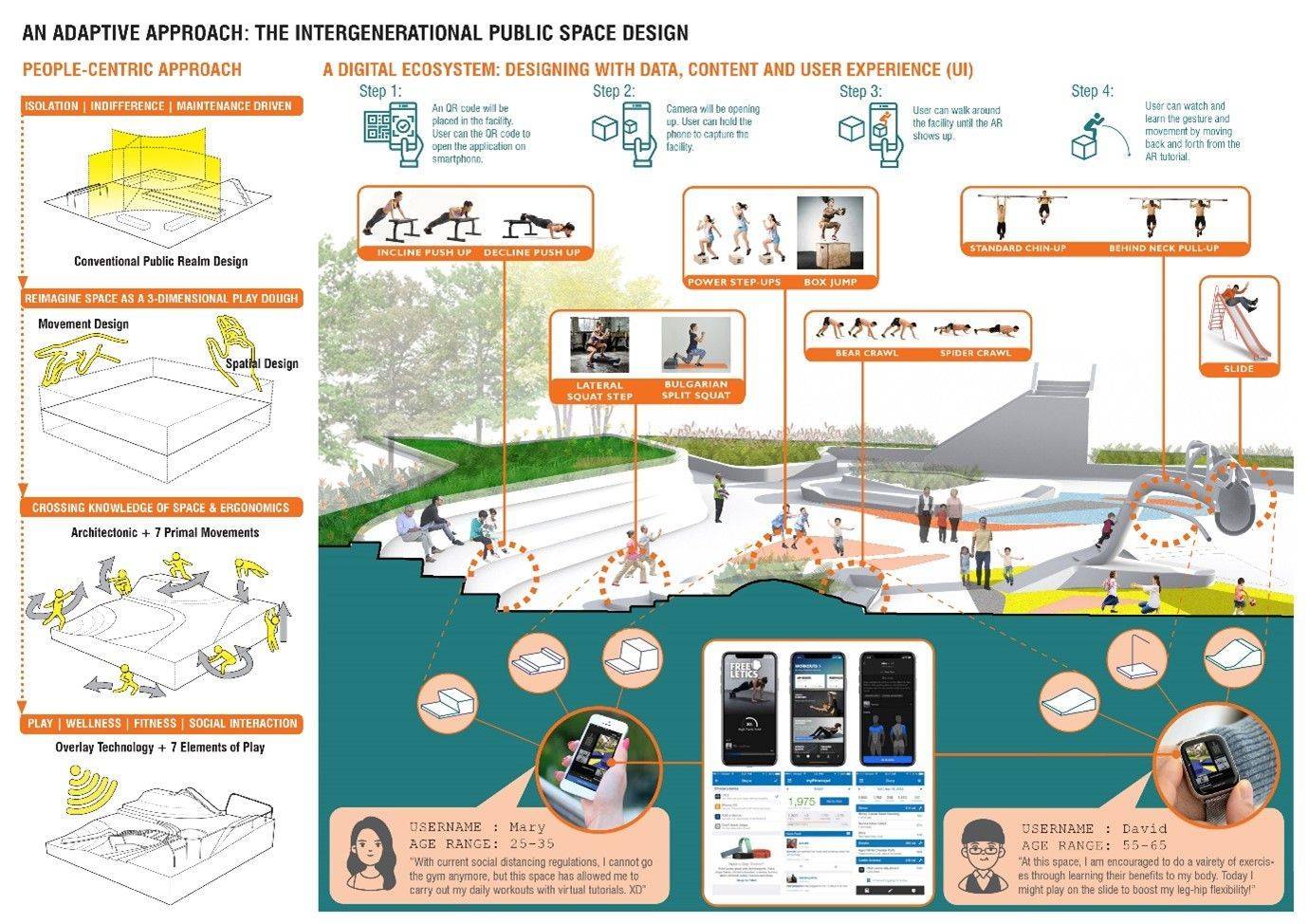

An adaptive approach: The intergenerational public space design

Successful public spaces need to be inclusive, accessible and safe, and representative of the diversity of groups present in our cities. They are a catalyst for everyone in society to participate in, to interact and to engage with, and to feel part of the community. As such, it is imperative to improve the performance of public spaces in terms of their usability and efficiency, facilitating accessibility and inclusiveness.

An adaptive design approach is not just a response to human needs; it is also a practical reaction to the dichotomy of doing more with less, which has become a tacit requirement in most public space design briefs. With increasing spatial demand and a shortage of supply, it is inevitable that we must design and operate public spaces that can serve as many purposes as possible to raise their efficiency. Therefore, combining active and passive open space into one should be a starting point, coupled with multi-purpose and flexible usage.

We can also anticipate a range of requirements and expectations coming from a variety of users, which will determine a divergent perception of well-being, from different social and physical phenomena. When it comes to promoting public health via a more active lifestyle, public space should always add in the wellness agenda, with an aim to move away from the segregation planning approach that creates individual silos of user groups which dominates our current spatial planning practice.

Applying a people-centric approach facilitates the understanding of human ergonomics, users’ requirements and expectations that can determine the design and operation of the next generation of public spaces. As such, public spaces of the future should aim to serve multiple purposes at once, whether that is fitness training, rehabilitation, children’s play, or more. At the same time, they should minimize the conventional application of standalone equipment, as they add maintenance pressure and limit program flexibility. Finally, this seemingly simplified space could benefit from a ‘digital ecosystem’, a digital dimension overlay onto our physical space to enhance performance, usability, inclusiveness and more.

Designing with data, content, and User Experience (UI) – a digital ecosystem

Key to adopting a people-centric approach in the design and operation of public spaces is having a clear understanding of how people anticipate, interact and benefit from that space; and designers can react onto the drawing board. This can be achieved through the trading, collection and analysis of data and content. The availability and interconnectivity of data and content allow us to improve the quality and experience of public space, from the earliest stages of design to the enhancement of a user’s experience, ultimately delivering better service to citizens.

A data collection system can also give real-time information about the use of physical space by embedding sensors into physical space, crosslinking people’s smart devices. The analytics of such data not only provide valuable information about the number and time of people using the space, but also other significant indicators such as health data. Collection of data could give governments crucial insights such as how active people are in one demographic. This could feed into future healthcare and spatial planning. Data could also, for example, allow health insurance providers to lower premiums to individuals with a more active lifestyle.

Crucially, the flow of content and data can enhance a user’s experience. For instance, when smart devices are capable of connecting with space, fitness users may connect their smart phone at a particular location and choose a precise training program (see Figure 2). Similarly, technology such as augmented reality (AR) could give a virtual demonstration on how to carry out the very training program within the space.

By matching a robust digital strategy with a people-centric design philosophy that incorporates inclusivity and public well-being, we will make an important advance toward a new era in urban design, an era of space-tech integration.

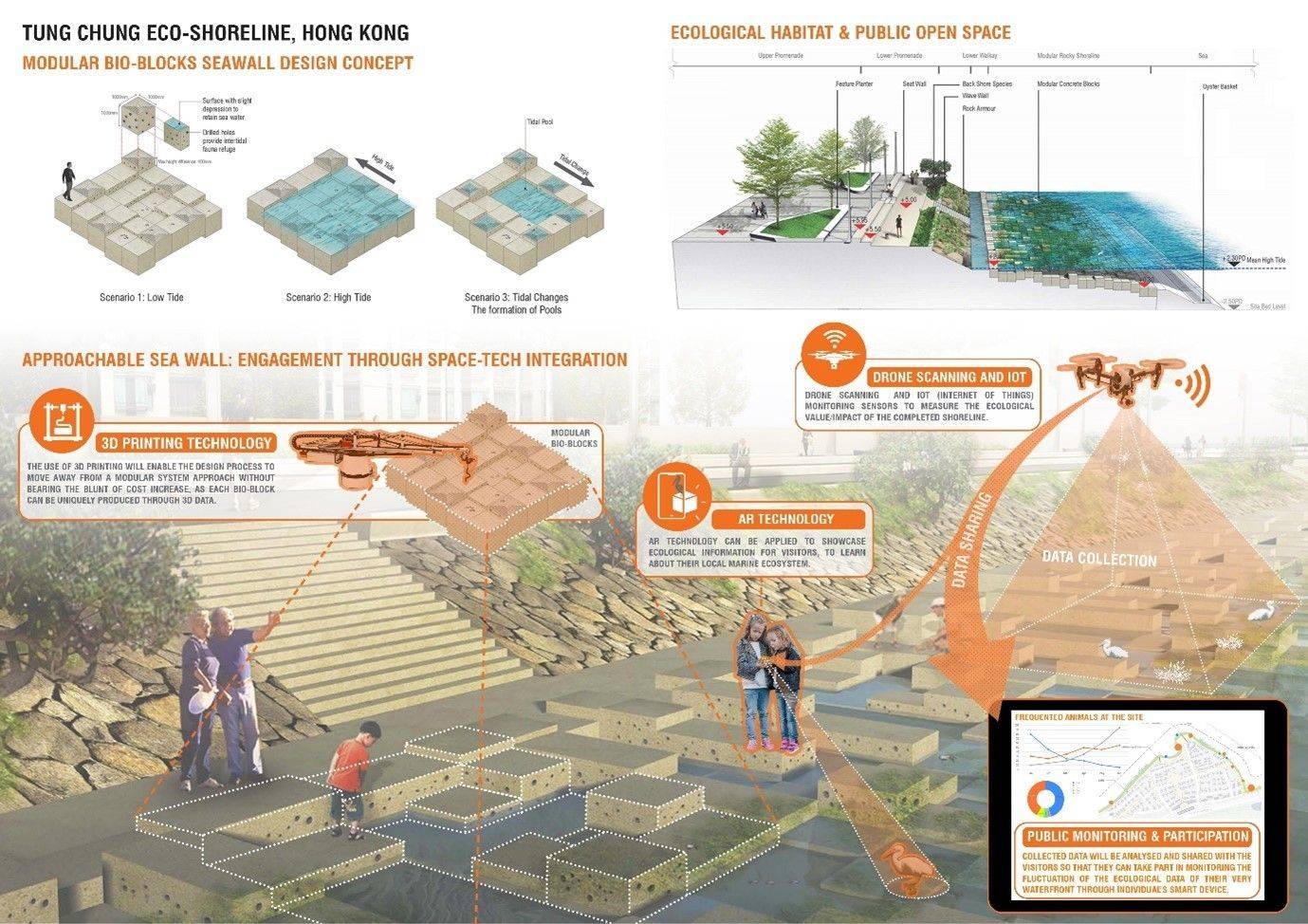

Case study – Tung Chung Eco-shoreline, Hong Kong

In mid-2016, AECOM was selected by the Hong Kong Government to complete the design and construction for the Tung Chung New Town Extension East (TCE), which would include the design of the world’s largest stretch of eco-shoreline.

Large-scale reclamation projects such as TCE normally use engineered sea walls to protect land from waves, storm surges and rising sea levels. While these are cost-effective options, they provide little in the way of ecological habitat or usable public open space. The key design objectives for the TCE shoreline included addressing these two shortcomings of traditional seawall design.

A main part of the TCE eco-shoreline was the rocky shoreline, a novel modular seawall design using cubical concrete blocks (bio-blocks) to mimic a natural rocky shore. The composition of these blocks captured tidal water and formed series of ecological rock pools along its extent, enabling marine creatures to thrive in this unique habitat.

Another mission of this design was to create an approachable sea wall, where people may engage within this setup to appreciate and learn about marine ecology (Refer to Figure 3) . This nature and people-focused approach was reflected in the decision to use a different seawall design that would provide resilience to coastal flooding, but also have much improved ecological value and serve as open space resource.

The resulting eco-shoreline design was undertaken in 2017 and shortlisted for the 2018 World Architecture Festival Awards, but the benefits of the digitally enabled, people-centric approach would continue beyond completion. The project extends further and demonstrates how current digital technology can assist with ongoing ecological survey/monitoring, and potentially add value in terms of public education and other environmental benefits.

Looking to the future, it is possible that data can be collected through various sources such as drone scanning and Internet of Things (IoT)-monitoring sensors to measure the ecological value and impact of the completed shoreline. The collected data can be analyzed and applied to future eco-shorelines with an aim for more a robust and effective setup. AR technology can also be applied to showcase ecological information for visitors, to learn about their local marine ecosystem and take part in monitoring the fluctuation of the ecological data of their very waterfront through their own smart device.

The arrival of upcoming technologies means that the approach implemented at TCE can be taken to the next level. For instance, the use of 3D printing will enable the design process to move away from a modular system approach without bearing the brunt of cost increase, as each bio-block can be uniquely produced through 3D data. For the rocky shoreline setup, this would allow the design to truly mimic natural rock characteristics, while creating a more sophisticated visual representation that also maximizes diversity in the marine habitat.

Similarly, the emergence of machine learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI) in generative design are now redefining what is possible for the built environment. AI-powered algorithms can be harnessed to simulate scenarios and evaluate impact in a way that is unmatched by manual design and is paving the way for even bigger leaps on nature-centric and people-centric designs.