A framework for measuring digital city livability

The concept of the city is a very human one, but what drove us to create them, and does it help to create a criterion for generating better versions?

For millennia, societies have been building cities with and without planning, forethought, and measurement. On the one hand, it could be argued that those cities that have grown organically without significant master planning have performed as well or as poorly as those that have. On the other hand, we know that the ability to see more clearly what is happening in a city is to also understand how to avert and respond to crisis, and to improve critical aspects of its performance. In some cases, we can even better understand why people fall in love with a city. Yes, we’ve even found ways to measure our emotional responses to cities.

Before the arrival of digital measurement and modeling tools, the concept of seeing into a city was more literal, and the purpose of our cities was more simplistic. For instance, the creation of vast avenues in European cities with medieval heritage such as Paris, Berlin and Barcelona allowed the authorities and city shapers, concerned with social unrest and the spreading of disease, to literally view the activity inside their city. Later, the emergence of urban or town planning as a profession started to rationalize how we measured and assessed our cities, but even this could not drive a strong unifying consensus as to what the purpose of our cities were.

Only very recently has livability started to be mentioned as a desirable quality of our cities. We are now faced with a range of significant challenges that are all becoming interrelated in a way never experienced previously, and ‘livability’ expresses the need to create cities that are more able to sustain the lives of all citizens. This in turn highlights not only the importance of developing people-centric digital cities as a means to deliver social, physical and environmental development, but also the crucial need of having a framework to evaluate digital city outcomes against those three elements.

Existing ‘livability’ measurement frameworks

Currently there are three primary, high-profile livability indices that are used globally to rank and compare cities to one another. However, the drawback of these indices is that in seeking to highlight certain aspects of each city, they are intentionally biased and do not assist the ongoing development and management of a city. For example:

-

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Global Liveability Ranking: This focuses on the challenges to culture, environment and services in cities larger than one million people. It is, however, a very basic overview of the essential services in a city and doesn’t necessarily take into account social and environmental aspects of a city’s performance.

-

Mercer Quality of Living Ranking: This looks at the access to basic human needs for communities with populations of 100,000 people to 1 million, as well as citizens’ access to basic needs such as housing, water and healthcare, but not elements that are typically seen in higher performing cities, such as general equality and access to recreation and to high paying jobs.

-

Monocle Quality of Life Survey: This aims to present an advanced ‘experience’ of the city for communities with more than 100,000 people, but it only looks at how a wealthy professional might experience a city.

Measure what you manage...but do we know what we’re trying to manage?

Toward a more robust system of measurement

To develop a more robust system of measuring and assessing the performance of a particular system, we’ll look at four more recent and comprehensive sources for understanding and measuring the outcome of the role of a digital city. These are dedicated to helping cities identify indicators for applying city management systems and to implement digital city policies, programs and projects. They are:

- OECD Measuring Smart Cities’ performance, 2020

- CITYKeys, European Union HORIZON 2020 program, 2020

- ISO 37122 Sustainable Cities and Communities – Indicators for smart cities and quality of life

- ISO 37120 Sustainable Cities and Communities – Indicators for city services and quality of life

These systems all underscore the importance of using data information and modern technologies to deliver better services and quality of life to all users.

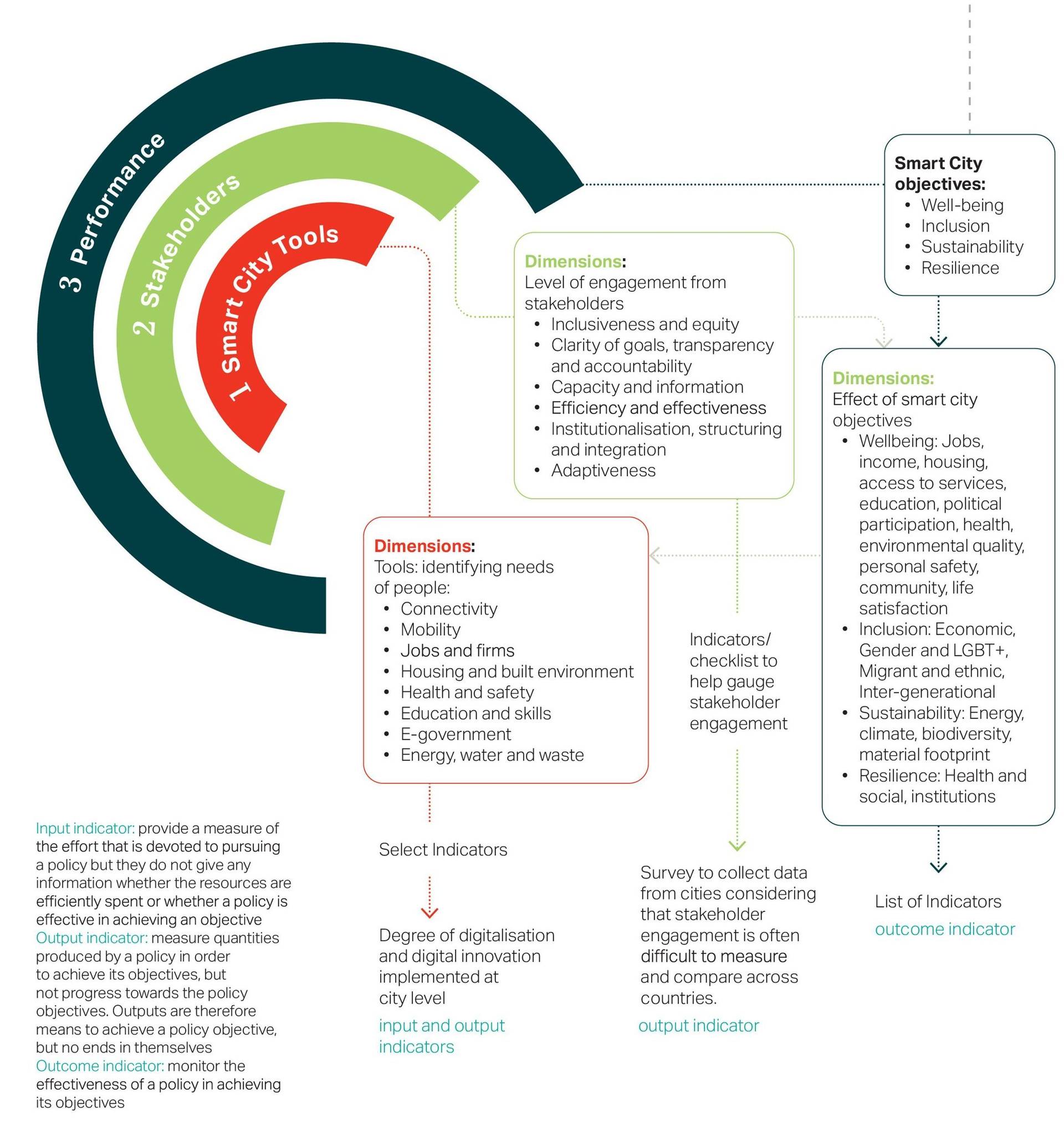

1. The OECD provides three levels of measurement, referred to as key pillars:

- The degree of digitization and digital innovation implemented at city level – the digital city tools (Quantitative data)

- Levels of stakeholder engagement (Qualitative data)

- Overall city performance against key digital city objectives: well-being, inclusion, sustainability, resilience (Quantitative data)

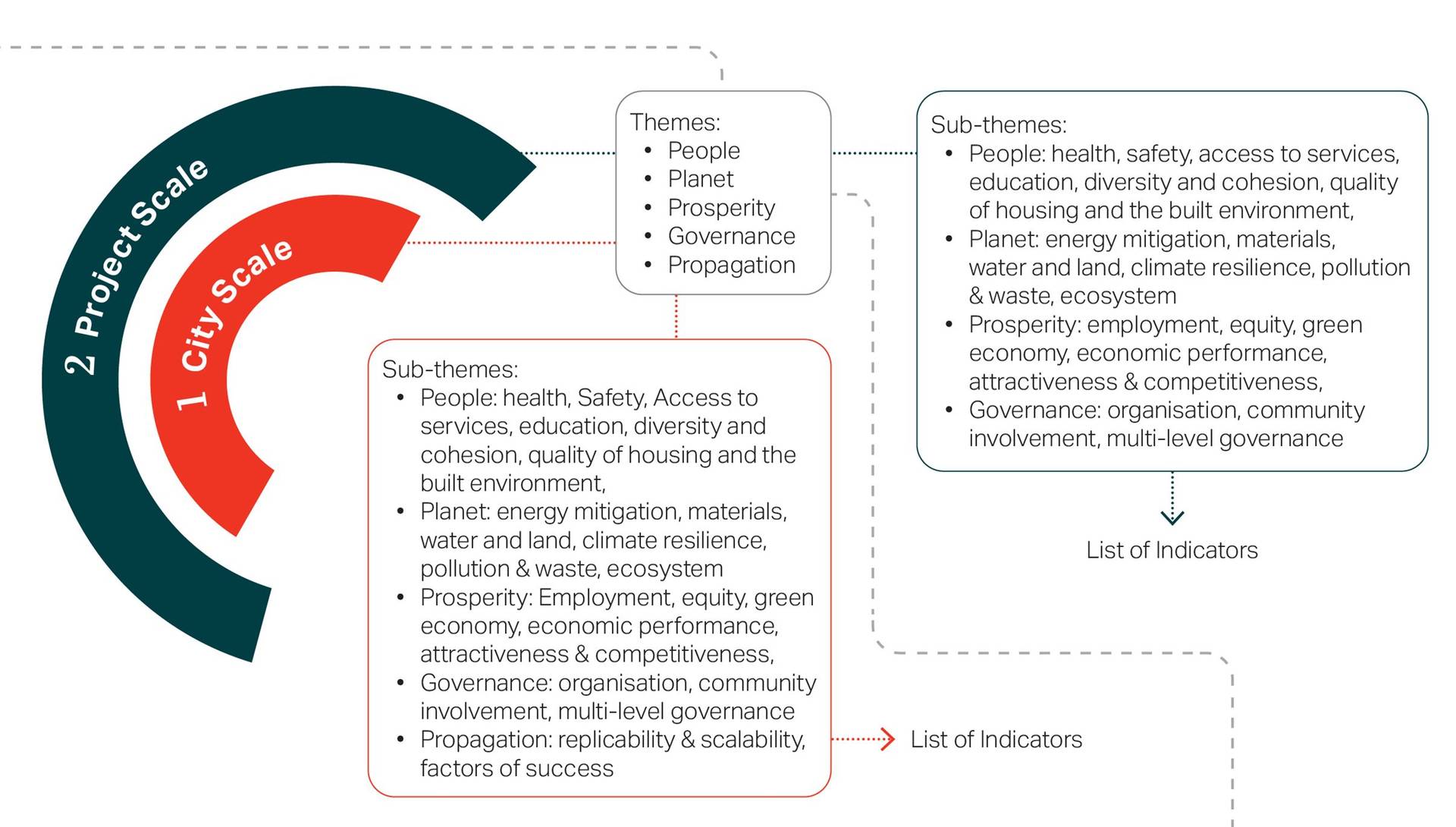

2. CITYKeys provides two scales of measurement: the project scale and the city scale. It is a holistic performance measurement framework for monitoring the implementation of digital city solutions, with the objective of speeding up the transition to low carbon and resource-efficient cities.

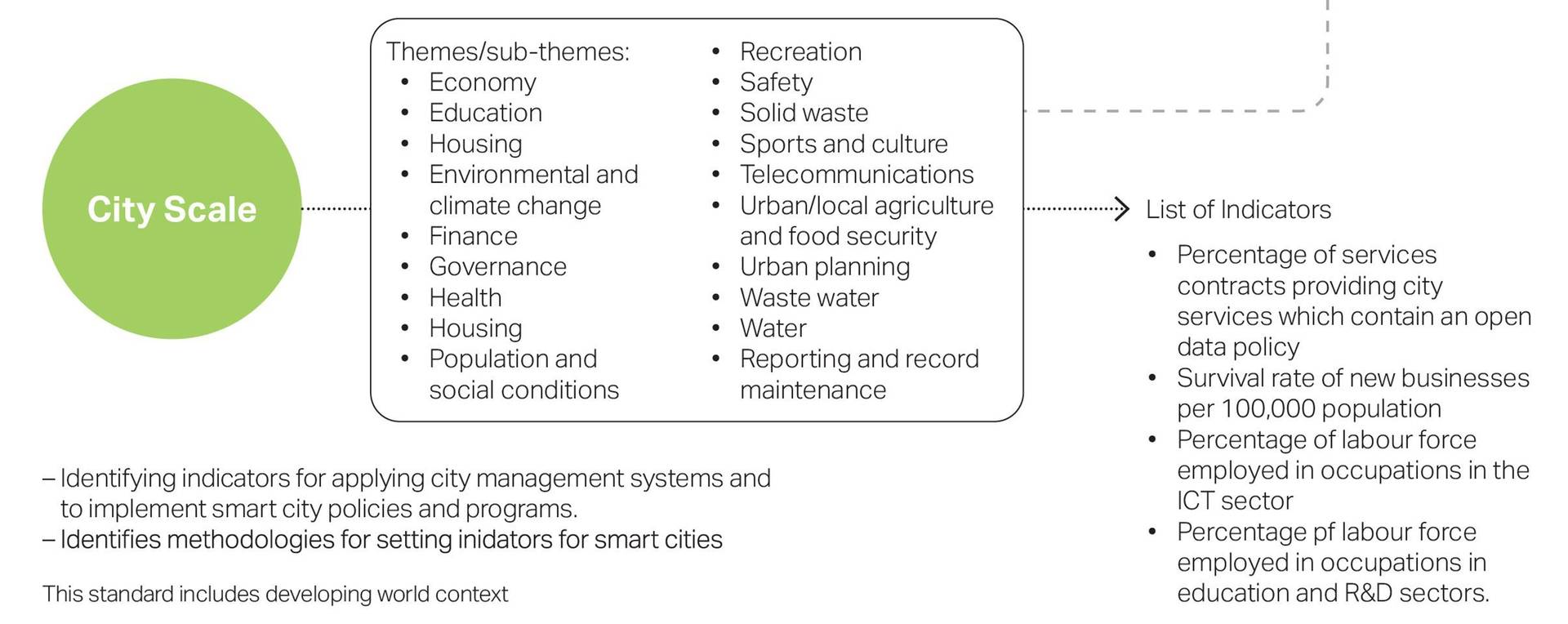

3. The ISO documents provide a list of indicators for cities designed to assist in steering and assessing the performance management of city services, as well as the quality of life/livability. Depending on a city’s objectives, it will pick and choose a set of indicators from these documents. Indicators are to be reported on an annual basis.

These measurement frameworks each provide lenses to measuring a city’s performance. However, what becomes critical for cities is selecting the appropriate indicators to monitor the progress of their city strategy and objectives. At the same time, it is important to note that not all indicators are equally suited for the full range of digital city projects or digital city policy focus.

Three elements of a responsive measurement framework

1. City strategy and policies What we have learned in the past decade of applying livability metrics to new and existing cities is that the bigger questions need to be answered first, starting with what do we want the city to be? AECOM’s work in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on the Greening Riyadh, NEOM and Al Ula projects have all shown that digital cities need to set out the governance aspects of the city, and to draw in and emphasize specific aspects such as the social and environmental values. The ability to then measure aspects of the new or existing city are guided by these policies.

Governments have now started to use metrics such as livability to both more accurately define the integrated outcomes they want to see from their city and as a framework to measure and monitor progress. Clarity across these metrics allows a better understanding of capital expenditures required and the frameworks will then guide and determine the use of digital technologies as enablers to achieve the aims of the livability strategies.

2. Objectives Once the city strategy and policies have been established, city managers should consider setting key objectives specific to each particular digital city project and, more broadly, to the city as a whole in order to guide their implementation priorities.

For example, for the Aerotropolis project for Sydney’s second airport, Western Sydney Airport, AECOM developed a list of digital city objectives based around policies from the federal, state, and local governments. This is important as it unlocks additional funding streams for deployment of digital city initiatives by engaging various stakeholders as digital city designers, as well as ensuring alignment of project objectives with the city’s broader priorities

3. Measurement In order to monitor a city’s performance and progress against specific objectives, it is important for cities to select key indicators. The CITYKeys, ISO and OECD systems are key frameworks to help identify relevant indicators. However, while frameworks and other digital platforms exist to help quantify these performance indicators, it is important to also consider qualitative aspects. For example, community consultation can capture the qualitative elements that address the community’s wants and needs. Similarly, information and communications technology (ICT) and digital platforms can enable improved forms of understanding the quantitative measures.

The frameworks discussed above can be time-consuming due to the manual labor needed to measure each indicator and consistently repeating the process. However, digital tools can provide performance insights on demand, which in some cases can be in the form of real-time data for constant monitoring.

Conclusion

-

All cities may be different, but they have similar needs. While the livability policies of each city will always be tailored toward the needs of the population, they will largely need to cover the same broad group of considerations.

-

Comparisons to other cities and how they have invested in specific infrastructure and programs, and their success or failure, should be better assimilated, assessed and used as more relevant test cases through a livability-type approach.

-

Clear targets for future performance should be set in order to drive capital investment strategies through each specific area.

-

Quantitative measurement data should be balanced with qualitative elements that together will give a more informed idea of how a community defines livability.

-

The power of digital technology should be used to predict how each aspect of the livability indices will respond to specific types of investment.

-

An intuitive and user-friendly interface should be utilized for the ease of communication and transparency. To initiate a project that involves major changes for the city and its citizens, data-driven decision-making is the key to acquire consent and disseminate benefits to the whole community.

-

We can measure almost anything. However, understanding first what we want to measure is key.